The Caribbean has no shortage of authors, however unless you seek them out or a friend recommends, you may believe that our stories aren’t being told. Maybe no in the mainstream, but it’s always refreshing to read about new authors who are writing about the cultural transitions of migrating from the Caribbean, an experience shared by so many in the Caribbean.

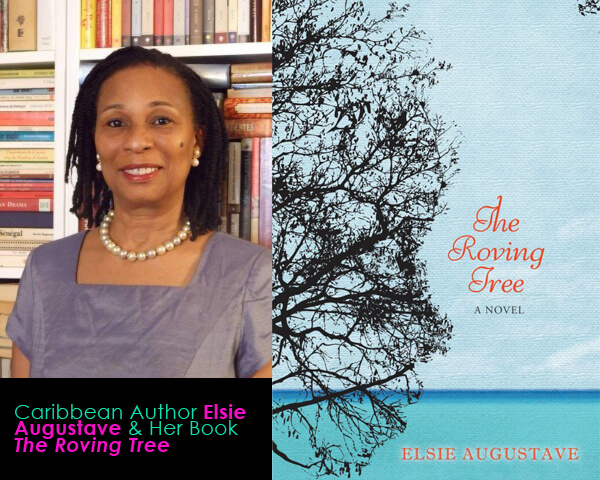

Elsie Augustave is a teacher and first time author with degrees from Middlebury College and Howard University in foreign language and literature. Her dedication to excellence in her field has been acknowledged through numerous international grants for continued studies allowing her to pursue her passion for culture in Senegal and France as a Fulbright Scholar. Augustave currently teaches French and Spanish at the renowned Stuyvesant High School in New York City, and is also a consultant for the College Board.

Augustave has been featured in a number of publications including the New York Times, Kreyolicious.com and making Essence Magazine’s summer reading list. I featured her book as part of my Mother’s Day Gift Guide this past May and had a chance to interview the Caribbean author. She spoke about penning her first book, her proud Haitian heritage and 2nd/3rd generation Caribbean battling cultural identity.

Tell me about your Haitian upbringing?

I grew up surrounded by maternal and paternal extended family, who often visited our home in Port-au-Prince. What I remember the most is the summer vacations with those relatives in rural Haiti, where I learned to appreciate folk life.

What were some of your challenges you had to overcome migrating to a new country at a young age?

The most challenging experience for me when I came to the United States was to break language barriers. At that time, bilingual education was in vogue and since there was a relatively small Haitian community in New York, the guidance counselor assumed that I was of Hispanic descent and sent me to a class where everyone spoke Spanish. While I learned English along with them, I also learned Spanish because they became my only friends, and they only spoke Spanish among themselves. In addition to that, some of the subjects were also taught in Spanish.

How did you come up with the concept for The Roving Tree?

When I decided to write a novel, I knew that I wanted to address life in rural Haiti as well as the issues of social and color prejudice, and class privilege. Likewise, I had often wondered about the life of a young Haitian who had been adopted by a French couple that took her to France and no one knew what had become of her. With that story in mind, I created a life for Iris, the protagonist of The Roving Tree.

Where did the title “The Roving Tree” come from?

During the early stages of crafting the novel, I woke up from a dream with the words The Roving Tree pounding in my head, and I knew right away that it would be the title of the book I was writing. The story subsequently was construed around the title.

The Roving Tree is your first book. Tell us about your writing process and how you decided you wanted to publish a book. What are some of the challenges and joys of writing your first book?

Writing The Roving Tree was a long and hopeful journey, but my determination and optimism kept me motivated. My biggest frustration was that I didn’t have enough time to dedicate to writing because of professional and personal responsibilities. However, the joy was tremendous once I crafted the novel. As for my decision to publish a book, I would say that I had for a long time considered becoming a writer and that publication is every writer’s dream.

What do you think second and third generation Caribbean-Americans can take away from Roving Tree?

Second and third generations Caribbean-Americans can identify with the theme of cultural identity in The Roving Tree. They may see themselves as Americans when outside of their home, but there are some cultural aspects that remind them that they are also tied to another culture.

Coming to the U.S. at an early age, are there any similarities between your life and the protagonist, Iris?

I was 12 or 13 when I came to the United States, but Iris was only 5. That makes a big difference, I think. Unlike Iris, I didn’t move to an affluent neighborhood in New York and didn’t attend private school. Up until I left to go to college, I had always lived where black immigrants lived. Yet, just like Iris, I used to be a dancer and have traveled to most of the places where Iris has been.

For second and third generation Caribbean-Americans, keeping connected to their Caribbean culture is expressed through the culture and traditions. Tell me about some of your favorite Haitian traditions that should be preserved through future generations?

Being the non-conventional person that I am, I don’t like to observe traditions because I like to do things on my own timing. However, I think it’s important for future generations to attend family gatherings, since it is where many aspects of cultural heritage are passed on.

How do you recommend Caribbean-Americans remain connected with their heritage even though they are living in the US?

The most obvious ways would be to go “home” as often as possible, to participate in cultural celebrations, and to read about the Caribbean as much as possible in order to find a greater sense of self.

What are you most proud of when it comes to your Caribbean heritage?

Like most Haitians, I am most proud of the role Haiti has played in World History as the first Black republic and the role of leadership the country played in the abolition of slavery in South America. I am also proud of other Caribbean men and women like Paul Bogle, a proponent of social justice in Jamaica and Solitude, the heroine and martyr of the 1802 rebellion in Guadeloupe.

Leave a Reply